Behind the Print with Steve Jessmore

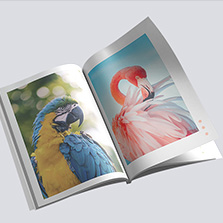

Welcome to another episode Behind The Print, where we bring you the creative stories of industry leaders shaping the world of professional printing. In this episode of Behind The Print, we’re joined by nature photographer Steve Jessmore. With a passion for photography, wildlife, and nature conservation, Steve walks us through how he uses the power of print and photography to help save endangered bird species and conserve nature.

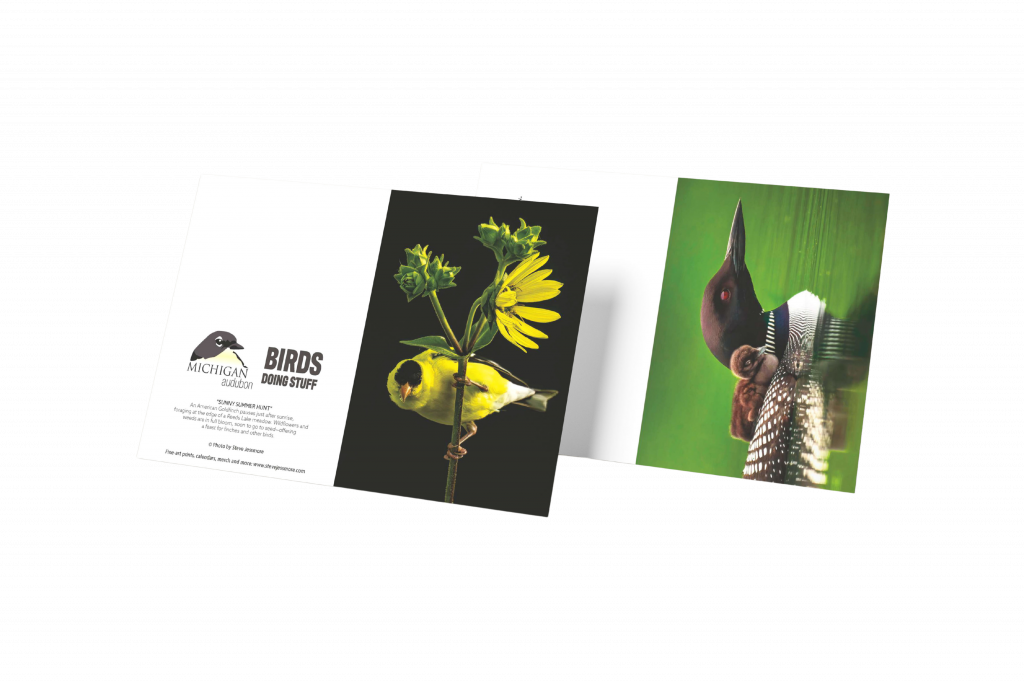

Connor Shields: Welcome back to Behind the Print Podcast, where we feature industry leaders and uncover the creative minds and their businesses within the world of professional printing. Our mission is provide you with inspiring actionable resources that elevate your business projects and accelerate your journey to excellence in profit and in print. Today’s episode is Birds Doing Stuff, and joining me here today is the owner, photographer, and recipient of multiple photojournalism awards. Steve Jessmore. Welcome to the podcast.

Steve Jessmore: Thanks, Connor. Glad to be here.

Connor Shields: Glad to have you. So if you’re ready, let’s just dive right in.

Steve Jessmore: Sounds good.

Connor Shields: So what made you get into photography, specifically wildlife and bird photography?

Steve Jessmore: It began in 2020 with COVID. I’d always been interested in wildlife, but never had an opportunity to do it. You know, families and raising kids and a job in photojournalism really prevented me from spending any time pursuing it. When COVID hit, I had nothing but time. I went from receiving over 100 invoices in 2019 to 6 in 2020, and was looking for something to do.

We had a cottage up north and we were restricted to stay at our homes, we spent a lot of time there. I had never been in a kayak before so I got in a kayak and started taking my camera out with me on the water. One morning around September, I was out in the kayak before dawn, and I had birds just buzzing me. As a photojournalist I knew I had to bring back pictures, but I wasn’t bringing back the pictures I was happy with. I remember saying “Game on”, and that was a moment I started doing bird photography and have been doing it with all my free time ever since.

Connor Shields: So you’ve obviously done a ton of photography from a kayak, from Wetlands, other less forgiving terrain. What sort of challenges do you have when you’re out getting pictures in these types of environments?

“One morning around September, I was out in the kayak before dawn, and I had birds just buzzing me. As a photojournalist I knew I had to bring back pictures, but I wasn’t bringing back the pictures I was happy with. I remember saying “Game on”, and that was a moment I started doing bird photography and have been doing it with all my free time ever since.”

Steve Jessmore: The weather’s probably the biggest one, just being prepared. Other then that, the biggest challenge for me was feeling comfortable taking my camera with 600mm lens on a kayak along with my other lenses along.

Another challenge I have is mobility and just seeing your subject and being able to capture it. I like to sometimes sit in one place like a blind and observe what’s around me. If I have an opportunity to stalk with a kayak and get a little closer viewpoint, I do it. But you have to really tread lightly, tread carefully. Be aware of every movement you make. Don’t do anything too fast or too erratic.

Connor Shields: So when you’re out on the kayak with that giant lens, obviously you’re pretty afraid of dropping it. Do you put a flotation device on it?

Steve Jessmore: No, I just have it on a strap around my neck. I don’t even use a dry bag or anything anymore, I just take the cameras out with me. I have a dry bag unpacked away in case it rains. I found as a photojournalist, your equipment has to be readily available if you’re ever gonna get the pictures. The 600mm lens is kind of my golden hammer. The first question I asked my insurance company was whether it was insured. I told them what I was doing and that it was gonna be on the water, and I would probably drop it at some point. And they said, “Nope, you’re insured”.

Connor Shields: So when you’re shooting, uh, you know, getting pictures of these birds, are there particular seasons that yield better results, like maybe spring or fall during the migrations?

Steve Jessmore: That’s absolutely correct. The spring and fall are the time with most movement and most mobility for most birds. Summertime is really, really slow. Like right now, the last few months, it’s just almost painful to sit out there, you know, and it’s hot. I generally only photograph for the first maybe two hours after sunrise, and I tried to get out in place well before sunrise. Oftentimes I’ll go back in the evening for a couple hours.

I do believe that the fall and the spring are great, but I personally love the winter the best. We have a cottage on a river in northern Michigan and we get a lot of the migratory birds from Canada. While I don’t truly have a favorite, but my one of my favorite types of bird is really ducks. I love ducks. I love seeing the different kinds of ducks, the different mating rituals and just the spunky activity when they’re on the water.

So as you said, fall and spring are a wonderful times for photographing birds. Spring’s always a problem for me though because my day job with college photojournalism is in full peak with commencements and end of the semester and things like that.

Its another challenge I have, I miss most of the migration because I have my other job. So kind of looking forward to scaling way back on the college and doing this and conservation work full time.

Connor Shields: What kind of conservation work do you do?

Steve Jessmore: I’ve been following like demise of a lot of little islands in our river. Erosion to shoreline, loss of habitat, that’s the number one problem facing birds and all wildlife probably right at this point, but especially birds and our river. The Torch River in northern Michigan is probably representative of many touristy kinda rivers. It’s almost like Michigan I-75 at rush hour. It is just boats all traveling north to Torch Lake and to the sandbar where they all gather during the day to fish and party. At the end of the day I’m trying to document that kind of the calm before that storm of activity.

I’ve spent more than 20 full days in the summer working on a bird called a piping plover. It’s a great lakes bird and they’re tremendously rare. There’s less than probably 200 adult birds in existence. They’re very tiny and they’re very susceptible to predators and to a lot of other things. This year there were a record of about 90 nests throughout the Great Lakes. I’m continuing that project with these birds right now.

Connor Shields: Okay. So the piping plover, aside from habitat loss, would you say that also maybe like invasive species has had an impact on them?

“I’ve spent more than 20 full days in the summer working on a bird called a piping plover. It’s a great lakes bird and they’re tremendously rare. There’s less than probably 200 adult birds in existence. They’re very tiny and they’re very susceptible to predators and to a lot of other things.”

Steve Jessmore: Not so much invasive species, but predators are gaining a foothold. Animals like merlins, coyotes, fox, anything that would go after a small bird. And they are quite small. They’re the size of a robin or smaller, and the babies are about the size of a cotton ball.

The babies are tremendously independent. As soon as they hatch and they’re run around on the beach and they can get stepped on, dogs off leashes, green herons, great blue herons, many, many, many things. They’ll eat these little guys in one little grab.

So it’s very difficult for them to survive. There’s a group with grants through the US Fish and Wildlife Service that provide a small protective structure almost like a dog crate. They place it over the nest to give the nest at least a little bit of protection. Problem is predators get smart and realize where the structures are, but there’s usually monitors with eyes on virtually every nest is.

Connor Shields: Like a nest cameras?

Steve Jessmore: No, like real people just out there volunteering and taking turns, making sure they’re okay. They also are educating people and roping off the nesting. This lets people know “Hey, this area is for these little guys”.

If the birds aren’t identified or people don’t know they’re there, it’s pretty easy for a dog to just grab one or even to step on one. They kinda huddle in footprints or in depressions sometimes, like when they’re afraid. So a lot of times if they see somebody coming, they might just sink down in a footprint and you step right on ’em.

Connor Shields: Yeah, it’s kind of like a baby fawn that hunkers down when you get close to it.

Steve Jessmore: Absolutely, absolutely. And especially since they can’t fly and they really can’t scurry very far or very fast.

Connor Shields: So, aside from ducks, what’s your favorite bird species to photograph?

Steve Jessmore: In all seriousness, it’s the one in front of me, and I really do feel like that. I don’t really go in search of anything per se. I just love coming up on a bird that I didn’t know was there, I see one at a distance and then maybe tomorrow I’ll go over to that distance and wherever it was and start out there. But I just, I love watching how they live their lives, how they take care of their babies, and how they get here and there by flying or by swimming. Or how they protect their home, their nest, and how they’ll fight off things much larger than them. One of my favorite pictures shows a red wing blackbird fighting a heron.

Connor Shields: I saw that with the Heron.

“I don’t really go in search of anything per se. I just love coming up on a bird that I didn’t know was there, I see one at a distance and then maybe tomorrow I’ll go over to that distance and wherever it was and start out there. But I just, I love watching how they live their lives, how they take care of their babies, and how they get here and there by flying or by swimming. Or how they protect their home, their nest, and how they’ll fight off things much larger than them.”

Steve Jessmore: Yeah. They’re just fierce and they’re not afraid anything. One week I got pecked on the head 5 times by the same Red wing

Connor Shields: They’re territorial.

Steve Jessmore: Very territorial. Plovers are very territorial for being a tiny little bird. It’s just a wonderful thing for me. I used to shoot pro sports a lot, so I was getting shots of people in action, people doing things again, not just sitting there posing for me. When I started photographing birds, the first challenge I had was getting past the perched bird, the bird sitting there. I want to get them hunting or grabbing that bug or actually get the bug and the bird in the same picture. Two birds is better than one in the same picture. They have emotion I think in some more ways to humans. A lot of times I think they’re bummed if one of their own get killed or get hurt or, being threatened by somebody else. Just the rituals. I love watching the preening and the feeding and looking for food and whatever it is, protecting their babies, just the different ways they do it.

Our rivers are notorious for huge fish and creatures like muskie and snapping turtle. I had. Snapping turtle just flip in front of me the other day not 10 feet away. These guys are just laying in wait for those baby ducks and baby geese. A lot of ducks and species have figured out ways to protect their babies. A female wood duck, a lot of times they’ll have their young on their back for the first week or two of. As they’re moving around through the open water and then the large fish can’t see or grab them. The same thing with loons. Loons will do that for the first couple of weeks. So it’s, it’s just to me, fascinating to see how birds and everybody adapt. Especially with loss of habitat. I’ve specifically watched two little islands right near our cottage. I didn’t pay much attention to them before. But I found pictures from 10 years ago these islands were 80 to a hundred feet long, and now they’ve disappeared. I watched them disappear from wakes and from people ramming their boats into them. Those are the sorts of things I’m watching as I photograph birds. I’m trying to tell those stories as a photojournalist would. I’ve done that with the Torch River. I actually approached a number of conservation groups and they took the ball and ran with it. The sheriff’s departments have also gotten on board. They’re starting to ask people to leave the areas and things like that. It all started with the power of a photo. That’s the kind of work I hope to do in the future. It’s, it’s not to say boaters are bad, I think we can all make wise decisions to protect what’s around us and maybe we can park someplace else for a little bit or not think like, we have to park wherever we want.

Connor Shields: Do you get much support from game wardens?

Steve Jessmore: I haven’t dealt much with the Department of Natural Resources, but like I said, we did approach the sheriff’s departments. They patrol the rivers and the DNR does too, and they’ve also started supporting trying to get people to stay off these areas.

I’ve made that pitch to not so much game wardens, but the powers that be in Michigan Egle and Michigan DNR and the Sheriff’s departments. They all see the value and they’ve all told me it’s totally documented to what’s happening. I think they’re happy to be on board and to know the problems there and to try to help to.

Connor Shields: So obviously you do a lot of work in wetlands and marshes. Do you go out and get, uh, wildlife photography in other types of environments like forests, meadows, things like that?

Steve Jessmore: Occasionally, but I tend to really love the water, so I’m really a swamp slash marsh edge of river kayak. You know, paddle in someplace where nobody knows I’m there and I can sit there in my own little world. That’s what I like. I do some forest photography, but not much. I’ve traveled a bit. I’ve traveled for Audubon down to Cumberland Island, Georgia for the Plovers. I actually photographed the same exact plover that I found in Michigan down in Cumberland Island. You can tell by the bands on their legs.

That’s one unique thing about these birds. They all have names.

I’m a newbie birder, honestly. Five years into it. I never had any interest before that. I’ve had, I’ve been propelled sort of into it by winning the National Audubon contest.

The first year I entered, I swept the professional division. The second year I entered, I also took most creative picture out of the 10,000 plus images. I never had any thought about doing it. I was posting during COVID, I was making people happy that couldn’t get out. That’s what I tend to think most of my photography, even as, as a journalist, I like to highlight stories that were positive and that gave people hope.

“I’m a newbie birder, honestly. Five years into it. I never had any interest before that. I’ve had, I’ve been propelled sort of into it by winning the National Audubon contest.”

I worked in Flint, Michigan even, which is the town that you know right away. So I did a column in Flint called Sense Community that highlighted those people, they were trying to make grassroots changes to make it a better place and still had hope. I feel the same way about my birds and about wildlife. If I can make people happy, that’s a really cool thing. Everything else sort of takes care of itself, it seems

One day I was paddling down the river before dawn and I put the paddle across my lap and I thought “I gotta do something with these pictures”, you know? Then I looked to my right, and honest to God, there was a loon three or four feet away just looking at me. It was just paddling right next to me. In that moment I really realized that was my sign and I had realized I needed to do something more. That was the moment where I really realized that they don’t have a voice, but I do. And I can do this kind of work and hopefully make people happy, make people aware, maybe make my backyard and the river a little bit better place.

The world needs to be taken care of. But if we all worried about what was around us and took care of what was around us, it would all add up cumulatively to make the world a better place. That’s my philosophy and that’s what I do with birds and that’s what I do. Again, trying to make people happy around me. Give ’em a bright spot in their days with all the negative news and the negative vibes.

I could do that forever and just try to make really cool pictures of the stuff that’s around me. I’m just finishing up a project around town here in Grand Rapids. So there’s a beautiful boardwalk at Reeds Lake in Grand Rapids, right in the heart of the city. I’ve spent over 200 mornings there. I started my day off there at. 5:30am / 6am in the morning. I’d go for an hour or two and get pictures, then I’d come home and edit or do the rest of my work.

Connor Shields: So going back to that place you mentioned in Grand Rapids, is that your favorite place to go kayaking?

Steve Jessmore: It’s my favorite place to just be patient on the boardwalk in all seriousness. I’ve taken the kayak out maybe, five, six times. But I really enjoy the boardwalk, its about 24o steps out into the lake, I won’t get bored. I can create a tremendous body of work from this boardwalk by watching the seasons and watching the movements of the birds and things like that. If I can do it with my lens, that means anybody, a person in a wheelchair or pushing a baby carriage can access the area too. I have a 12 power lens. So someone with 12 power binoculars can see the same things too.

You could have see every single moment.

I mean, I’m sure I could have got more diversity and variety in certain areas of the lake if I would’ve kept going there and all that kind of stuff, but. You know what I saw probably 90% of it right from that, that couple hundred steps. And it was a great way to see the mornings and meet people and talk to people and spread the word.

I’ve made so many cool friends and I’d see the many of the same people walking day after day. My favorites were these two ladies I’d see on most days. I’d be down in camo and be like leaning by the railing and just sitting there and just watching. They’d see me from down the boardwalk and yell, “Hey, have you seen the Eagle yet today?”

I’d say “Yeah about 10 minutes ago” you just gotta be quiet and watch. So it’s about trying to educate and getting people to understand we’re not watching the television program and that these animals are wild. You just have to use some patience and some respect. And I met so many great people there and had so many great experiences.

I feel like I’m sort of a representative of nature, I’m telling people what I’m seeing and how valuable this is and how cool it is.

Connor Shields: How does wildlife photography differ from taking pictures of people?

Steve Jessmore: Until recently, I’ve been a people photographer my whole life. Pictures couldn’t be published without a person in them 99% of the time. It’s kind of the opposite now. This is the first time I’ve ever owned my photography, this wildlife stuff. I’ve always worked for somebody else and they all own my copyrights and my images. I can’t even show them to people. So again, the Birds Doing Stuff came from this sort of situation. When I won the Audubon award, I couldn’t tell anybody for two months and three days before the deadline. I finally told one of my buddies when we were on the deck drinking bourbon up north, watching the river go by, and I said, “I won this National Audubon contest. Out of 10,000 entries, I won first and the only honorable mention”. I’ve never even had a wildlife picture published at that point. We talked a little bit and he said “your pictures are just different, they’re birds doing stuff” he also said “you take a little bit different approach than most of the photography I see at this point”.

“When I won the Audubon award, I couldn’t tell anybody for two months and three days before the deadline. I finally told one of my buddies when we were on the deck drinking bourbon up north, watching the river go by, and I said, “I won this National Audubon contest. Out of 10,000 entries, I won first and the only honorable mention”. I’ve never even had a wildlife picture published at that point.”

For me, it’s kind of like I have that lowest common denominator in my mind. If I look in a picture, it’s like, well, “is that bird doing anything?” It’s been a great challenge, a great goal and a great path to learn trademarking. To just take something that I own and see where it can go. So I did two coloring books, two calendars, I did note cards, I did all this stuff, and that’s where PrintingCenterUSA comes in.

Connor Shields: We appreciate it.

Steve Jessmore: I have done nearly five calendars through you guys in the last few years, and I’ve worked my way up to about a thousand calendars a year now, and this year it might even be more the way it looks. So I’ve really appreciate that support I’ve gotten from all you guys. In all seriousness, that give me all these different options, you know, that I don’t have to build them, I don’t have to the inkjet cartridges and replace them every 10 minutes sort of thing. It’s all at a price that is marketable and I’ve appreciated that.

Connor Shields: Oh, absolutely. We appreciate the business. So going back to what you had previously said that major photography award, are there any other milestones that really defined your career as a wildlife photographer?

Steve Jessmore: I’ve had multiple covers now on National Audubon Magazine, but this last cover in story was a big milestone for me.

I got a call from the photo editor that said I won the National Audubon contest and had a conversation with her where I mentioned I was a photojournalist. We talked some more and she says, “if you ever have ideas, why don’t you pitch them to me?”

So I started pitching her ideas and now we have a regular call virtually every month in with the national photo editor of Audubon. That turned into her seeing both my work ethic and my work, and not just the contest work, but everything I do. One day, she contacted me with a local story that she said, “would you like to shoot it?”

And I’m like, “heck yeah!” So that story gave me about 10 days of work in Michigan and then a trip to Cumberland Island, Georgia in the wintertime. It ended up being eight pages of photos in a cover story in the magazine, which to me is really cool. I was always a publication journalist, but mostly newspapers and I would always work on stories.

So those are the kinds of things I really love doing. Finding a solution, finding a positive out of the efforts that we all put in with the ups and the downs along the way, and hopefully having a successful outcome. And that’s what I’m trying to do with the birds now. So these milestones, I don’t know what the next milestone quite honestly could be.

Having won the National Audubon a couple times, I don’t even enter anymore. I think just continually being published. I think my next goal is I’m working on a multiple. Things that I hope can be books. That’s part of the Plover plate right now that I’m doing, and I really hope that’ll be the next milestone maybe in my life.

And other than that, I just really hope to see like my islands survive and up north that would be a milestone to get people on board and realize how important they are to sway public opinion.

Connor Shields: When it comes to the book of the piping plovers, we can definitely help you reach that milestone.

Steve Jessmore: Well, all I may have to contact you guys. I’m really hoping that’ll become a reality soon and it won’t be from lack of trying. And that’s the thing I think with Photography that most people don’t understand – to have that patience for that shot. I have a no cell phone rule when I’m out. Like you’ll rarely see me looking at a cell phone and taking my eyes away from whatever I’m trying to watch. I just like truly get amazed every single day. My wife actually, every day she’ll say, “how was your day?” and I’ll say “ah, it’s the best day ever”. And she’ll laugh at me and “you say that every day”. And I say, “It was just different than the other best day.”

Connor Shields: So, a few more questions for you. What are some challenges or obstacles that are holding you back right now, either like personally or professionally?

Steve Jessmore: For me it’s the balance of making money versus making the pictures that I want to make. Time is always the challenge. I think time enters into so many different categories. The one category would be knowing how to do something I haven’t done. Like doing a book and finding a publisher, distribution network, and the logistics. I’ve done the logistics of building books and having you guys print them.

I’m a one man team, like many people are nowadays, I want to be the creative, but then the other side of me tells me I got to buckle down and do my quarterlies or, or I have to add up all my receipts this week, or I have to get all my print orders out. I got to do all these things that keep my butt in the chair.

In addition to all of that, I need to balance the time with my spouse and my family and all that sort of stuff. So there’s all those like things that tear you one way or another, but as a sole proprietor, a person that really depends on myself to make all my income and do everything I need to do.

Connor Shields: Yeah. Going back to what you were saying about the shutdown where when you have nothing but time, I can definitely see how that really catapulted your career into where it is now.

Steve Jessmore: It sure did. And it was thankful to my wife to sit me down and say, “look man, this is a gift of time. You are so blessed to have this time. You need to make the best out every day.” Who knows how much time God’s gonna give you, you just need to find what you always wanted to do and do it. And honest to God, when she said that to me, my mouth dropped. I’m like, “I don’t know what I always wanted to do.”

I had no idea at that point, and it took me a few months to figure that out. But I’m glad she gave me that talk because I had that time. And she’s still that way. She’s still like “yeah, you’re good. Go. Just go do whatever you need to do and I’ll be here when you get home.” And it’s like, wow, this is wonderful. I never was fortunate like that. Most of my life. So

Connor Shields: Yeah, the, the same thing kind of happened to me during the pandemic. I went from having no time at all to all the time in the world, so I can definitely relate to that.

Steve Jessmore: It’s really easy to get lost in all that time in the world. Like it just tasses and you do nothing with it.

Connor Shields: And then after it passes you, you’re thinking “What happened? Right? What did I do?”

Steve Jessmore: I’m so blessed that I locked onto something. It took me a while, but I always thought about that talk. It took me a little while to get my wheels turned in the right way. But once I did, I never looked back. Once those ducks flew over my head and I couldn’t get ’em, honest to God it was game on. I came up with a plan to get better at what I was doing, and I did. I didn’t know that was my purpose at the moment. But it was something that fulfilled the time and gave me a new creative outlet. It didn’t take long for it to like really get weighted that this is the most important thing I want to do. Especially tying in the journalism and the conservation and all that stuff with it. I have a biology degree too from college, way back when I’m sort of mixing all my art, my biology, my journalism, everything together for the first time in one path. The weird thing is I never had a business class in my life, and so these sorts of things are the things that oftentimes I get lost in and feel like I’m spinning my wheels.

Connor Shields: Yeah, the, the devil’s in the details. So I think I already know the answer to this next question, but if you had a day completely free to spend however you like, how would you spend it?

“I’m so blessed that I locked onto something. It took me a while, but I always thought about that talk. It took me a little while to get my wheels turned in the right way. But once I did, I never looked back. Once those ducks flew over my head and I couldn’t get ’em, honest to God it was game on. I came up with a plan to get better at what I was doing, and I did. I didn’t know that was my purpose at the moment. But it was something that fulfilled the time and gave me a new creative outlet.”

Steve Jessmore: I would definitely be creating something. I think I would either be editing photos all day long or be out on the water at 4:30 in the morning and stay out the majority of the day. That Kayak is the probably best tool I ever got in my life. It gave me mobility and opened up so many new possibilities.

It’s almost like you’re playing a Zelda game when you go through the secret passageway. Sometimes I’ll go through a clearing and say “oh my God, look at this little pond back here” or “look at this little ecosystem”. I looked at lilies the other day and then I zoom in on it and see that there’s like countless bugs in this little ecosystem on that Lily too.

Connor Shields: When you’re out there on your kayak, are you trying to blend in like you’re on land? Like you mentioned you were all wearing all camo on land. Is that also case on your boat?

Steve Jessmore: Yeah, totally. I never felt legit enough to wear camo because I never hunted, or outdoor stuff, but I always thought that’s pretty cool. Then I started doing a little bit of wildlife photography and I bought a pullover with camo and I went out the next day. It was like night and day. It was so different. The birds like didn’t see me and I had the hoodie up and all that. When you’re out in nature you like you belong. I have camo for all seasons but I still need is a good walk around pair of camo pants. That’s next on my list. But I think I got everything else.

Connor Shields: I recommend you take a look at Sitka Gear Camo. In my experience, that stuff works like a charm.

Steve Jessmore: I’ve got a ton of it. Yeah.

Connor Shields: That stuff works so well. In my experience, I’ve have had animals walk right up to me while I’m wearing Sitka gear.

Steve Jessmore: I was in the driveway in full camo and everything and I would walk 10 feet and stop and walk 10 feet and stop and stand there for a minute or two. All of a sudden I just turned and there was a doe, not like 10 feet from me.

Connor Shields: Yeah, I can, I can definitely attest to the, the effectiveness of that camo. Well, I have one last question for you. How can our listeners get in touch with you, learn more about your work, or maybe even collaborate with you on a project? Yeah, I’d love that. I’m on Instagram @sjessmo. You can also check out my website, it’s just www.stevejessmore.com. You can type in birds doing stuff, and it’ll take you to www.stevejessmore.com. So that’s kind of cool too. I’m also on Facebook, I’ve built really a good following. You know, I think I sold calendars last year in prints to 38 states just off Facebook and off my Instagram and stuff like that.

I would be more than happy to help anybody with a question or collaborate with some great writers or some other great photographers. I hope to do some more seminars and workshops.

Connor Shields: Yep. All right. Well, I’d say that’s a wrap on another episode of Behind the, uh, print. Let me say that again. Well, I’d say that’s a wrap on another episode of Behind the Print. Thank you, Steve for joining us, and thank you to our listeners as we enjoy explored the artistry and innovation of the printing world. Remember, having a strong vision, building the right strategy, and using tools like Print to amplify your message, will make your brand stand out from the crowd. If you enjoyed today’s episode, be sure to get your sample pack today from printing center usa.com and share it with your fellow business enthusiasts. Until next time, keep those creative sparks flying. And remember, there’s always more to discover behind the print.